What should you drink at a piano recital?

By

David YangWe were discussing Evren’s upcoming recital and he wound up pairing each piece with an appropriate libation.

Have you ever done something that screwed over your boss but was to your benefit? That’s what baroque composer-violinist Heinrich Ignaz Franz Biber did. He got away with it, too.

In the summer of 1670, Biber’s employer, Prince-Bishop Karl II von Liechtenstein-Kastelkorn (these guys have really long names) sent him 250 miles to Innsbruck to purchase new instruments for the court. He never made it, electing to take a detour to Salzburg where he arranged a meeting with the Archbishop and promptly offered up his services. The Archbishop was more than happy to accommodate the young virtuoso.

Prince Karl was decidedly not pleased but did eventually forgive him, and Biber dedicated several works to his former employer, perhaps recognizing he’d been a jerk. But in the words of Liberace, he probably “cried all the way to the bank.”

Who was Biber, a composer that Paul Hindemith wrote was “second only to Bach.” He was a Czech-Austrian who put a sledgehammer to traditional violin technique and composition, paving the way for Bach and Corelli (whose works also feature prominently on the upcoming Winter Baroque concert) and even Bartók.

One of Biber’s greatest works was his Sonata Representativa, written just before he bailed on Prince Karl. As with much of his music, it is a technical tour de force from a man comfortable challenging basic assumptions about how a violin should be played. Audiences of the era must have been dazzled by his pyrotechnics; you can understand why the Archbishop snatched him up.

This was a feverish era of European discovery on all fronts. The 17th Century saw the establishment of the first permanent English settlement in Jamestown, Virginia, while up north Samuel de Champlain was founding Quebec City. Dutch explorer Abel Tasman discovered a huge island south of Australia, and the first European reached Tibet. (Of course, things didn’t look so rosy from the indigenous populations’ point-of-view.)

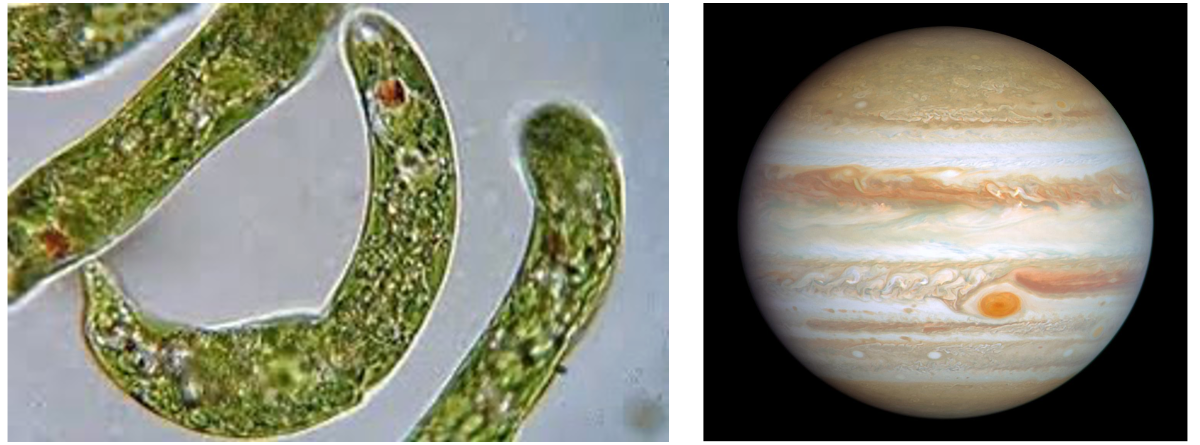

As European explorers were pushing physical frontiers, backyard scientist-explorer Antonie van Leeuwenhoek took a drop of water from his local pond and, looking at it under his microscope, discovered a miniature world of “animacules”; Galileo turned his telescope to the heavens and discovered moons revolving around Jupiter, putting paid to the idea that the earth was the center of the universe (no, this didn’t work out so well for him); Isaac Newton was expanding frontiers in math and physics, developing calculus and the laws of motion and gravity.

Meanwhile, the Catholic Church was striking back against the Protestant Reformation, sponsoring new waves of dramatic art. Monumental architecture like the basilica of St. Peter’s left the masses in awe, and painters like Caravaggio were producing stunningly emotional canvases that swirled with movement and light. Compared to the idealized classical lines of the Renaissance, this stuff was real.

It was in this heady climate that the iconoclast Biber burst upon the scene. Like Leeuwenhoek’s microscope, he turned a finely-tuned ear to the natural world and used the violin to imitate the sounds of 17th century life – the crow of a rooster, the sound of soldiers marching past. He also pushed the boundaries emotionally of what music was willing to express. I can’t emphasize enough how radical this was. Instrumental music was in transition from devotional music that looked upward to the heavens, to a secular art form gazing at the world around it. Nowhere is this more apparent than in Biber’s groundbreaking Sonata Representiva.

One of the earliest examples of instrumental program music, Sonata Representiva is comprised of nine miniature movements depicting (in order) a Nightingale, Cuckoo, Frog, Cock & Hen, Quail, Cat, and a Musketeer's March. Come to Winter Baroque at Immaculate Conception on Sunday, December 21 at 3:00 and imagine yourself sitting in a pew in Salzburg, Austria, hearing all this for the very first time.

Maybe it will make a Beileber out of you, too.

David Yang, Artistic Director

By

David YangWe were discussing Evren’s upcoming recital and he wound up pairing each piece with an appropriate libation.

By

Peter MiyamotoTo enter the world of Carnaval is to enter the complex world of Robert Schumann’s psyche.

By

David YangListening to this program is to be an intrepid explorer of feelings in music.

NCMF relies on the assistance of corporations, foundations, and most importantly, you.

Make a GiftVolunteer